If you want your vegetable garden to really feed you, knowing how much to plant is essential.

It’s one of the biggest questions in vegetable gardening—whether you’re growing food in a warm, year-round climate or in a cooler region with a short growing season. Planting too little leaves you without enough fresh produce. Planting too much turns into the classic “zucchini overload” that every gardener knows all too well.

In my gardening courses here in the Serra de Monchique, this topic comes up again and again, especially for people who want to be self-sufficient.

New growers want to know how many plants they need for a steady harvest. More experienced gardeners want to fine-tune their garden plan so they can eat from the garden for as much of the year as possible.

But here is the truth: how much to plant depends on three things—your climate, your family’s eating habits, and whether you want only fresh harvests or also preserved food for the winter.

Two Planning Strategies for Knowing How Much to Plant

There are two strategies that I use for planning how much I grow. Both start with the needs we have for our dinner table.

Method 1 — Calculate What You Need for the Whole Year

This is a bit easier when you are just starting out. It gives you a fair overview of what you will be planting throughout the year. Seeds, if you want to order them, can be ordered all together at the beginning of the year, which saves postage costs.

This method is also more suited to cooler climates, since you have a clear growing season with a start in early spring and an end around October or November.

But having said this, it also works fine in a milder climate like our Serra de Monchique (southern Portugal). So when you are new to vegetable gardening in a mild climate like the south of Portugal, this is the one to try first. Use this method first, get some experience, and then decide if you want to use Method 2.

Method 2 — The Monthly Planting Rhythm

Once you have a feel for how long vegetables take from seed to harvest, you can switch to a monthly planting rhythm. Instead of calculating your yearly needs, this method helps you plant just enough each month to feed your household.

This approach works especially well in mild or Mediterranean climates like the Algarve, where you can grow something in the garden every month.

Before we dive into how each method works, we will look into why it is actually so complicated to get the amounts of vegetables right for your dinner table needs.

Why It’s Hard to Know Exactly How Much to Plant

Even experienced gardeners struggle with this question.

And to be honest, it’s hardly possible to get it exactly right, especially when you are just starting with self-sufficiency, so we always go for an approximation. It’s more a learning path than a “get it right straight away”.

Knowing the complications will help you on the way.

So what actually makes it complicated?

Different Vegetables Produce in Different Ways

One-Time Harvest Crops

Plants like lettuce, Chinese cabbage, broccoli, etc., just produce one harvest. You sow or plant them, they grow in 4–6 weeks, and you take them out as a whole and off they go into the kitchen.

Long-Season Producers

Other vegetable plants keep on producing for some months, like tomatoes, aubergines and zucchini. They are planted in spring and carry their fruits in the summer for two or three months, depending on the climate you’re in. The size of the harvest depends on the amount of fruit that each plant carries and how many plants you have planted.

Cut-and-Come-Again Crops

Leafy plants like Swiss chard, collard greens, and kale are harvested bit by bit while the plant regrows. Swiss chard can be harvested over the whole winter. Kale and collard greens can be harvested over the summer or winter depending on where you are on the globe.

With this group of plants you have to be aware that plants grow much faster in late summer and early autumn than in late autumn and winter. You will have to adjust the numbers accordingly, as you will see later in the blog.

Steady Harvest as You Go

Carrots are a bit in between. You do harvest them one by one, but usually you sow so many that you can keep on harvesting them for two or three months. They just grow bigger until they start bolting. Some types of onions and beetroots also belong in this category.

Perennials in the Vegetable Garden

You might also have perennials in your vegetable garden, like asparagus or rhubarb. These will all have their own harvesting time. These two are mainly harvested in spring.

Different Crops Produce at Different Times of the Year

Actually needless to say, but it’s still worth pointing out. Every vegetable has its own ideal growing time of the year.

Let’s dive in

Okay, now we know the different ways plants produce a harvest, let’s look into the two basic methods that I use to plant enough vegetables to serve a meal from the garden for every day of the year.

You will see that knowing what I just wrote above comes in handy.

Method 1 — Calculate What You Need for the Whole Year

Remember, this method is the easier one and it fits best in cooler regions, although it would also work in milder climates. So when you are a starter in a mild climate like the south of Portugal, this is the one to try first.

We will go through the method step by step.

Step 1 — Track What Your Household Actually Eats

Before you can know how much to plant, you need to understand what your family actually enjoys eating and cooks with regularly.

1. Make a List of Your Family’s Favorite Vegetables

Focus only on vegetables you actually eat.

There’s no point growing something that never ends up in your meals—it only leads to waste.

2. Turn That List Into a Simple Seeding Calendar

For each vegetable, write down:

- When you sow or plant it

- How long it takes before you can harvest

- Until when it will keep producing

A simple sketch or table is enough. You’re basically mapping the year so you can see which vegetables are available in which months.

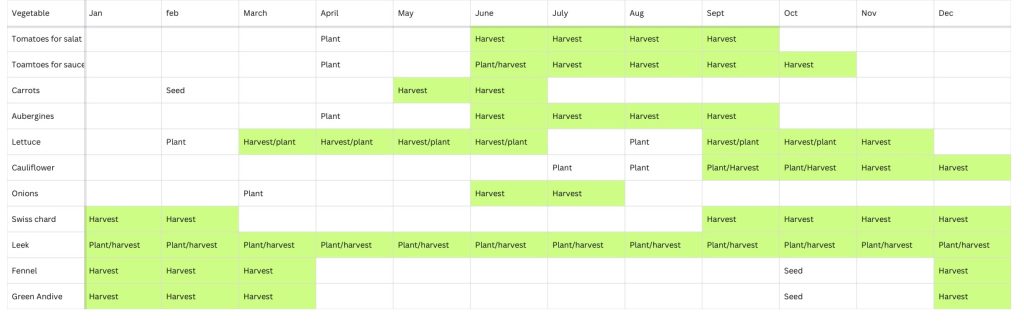

In the picture you can see an example of the sketch in a spreadsheet. This is not our whole calendar, and it only applies to our vegetable garden in Monchique. If you garden in a similar climate, the timing will be close; otherwise it’s better to make your own. You can use a regular garden planner for your area as a basis, which you can fine-tune for your own garden.

As already mentioned, it is really hard to get the timing right straight away. You will need to adjust your own calendar every year until you get it more or less right for your garden. Still, there will always be some variation per year, but that is manageable.

3. Read From Your Calendar What Is Ready for Harvest

Example 1: January

So let’s look at January. We can harvest Swiss chard, leek, fennel and green endive.

Sure, you can add some more variety if you think it’s boring, but just for the sake of the example let’s stick to those.

There are four weeks in January and we are two people. Say every fourth day we will eat a leek, that means we will need about eight leeks (planted in November).

The same numbers apply for the fennel (sown in October), green endive (sown in October) and Swiss chard (it grows wild in our garden).

We will have eight leeks, eight fennel, eight green endive and lots of Swiss chard for the kitchen in January, which covers our needs in this example.

I’m not going to sow only eight fennel or endive plants, because once they are ready, we’ll harvest them over three or four months.

So in total you will need 24–32 plants.

It basically means I’m going to sow a little row in a sowing bed of 50 cm. From there I will transplant them into a longer row to give the plants more space to grow.

Don’t stick to 24–32 plants; sow a few extra, around 40 plants or so. Some plants might get eaten by slugs or not survive for other reasons. This way you are also covered when the speed of growth goes down because the temperatures drop.

Example 2: July

Let’s see how the same method works out for July. We are still two people.

In July we can harvest: tomatoes for salad (big and juicy), tomatoes for sauce (Roma), carrots, aubergines, onions, leek.

Tomatoes for the Summer Salad

We like to eat tomatoes in salads in the summer, but not every day. So I estimate we will eat salad tomatoes twice a week, and we need about two big tomatoes for every salad. That makes 2 x 2 = 4 tomatoes a week.

Tomato plants that produce these big fruits do not produce very many per plant. So I think we will need two or three plants of those to have our 4 tomatoes a week. These two to three tomato plants will give us our tomatoes for our salad from June to September.

Tomatoes for Sauce

For sauce tomatoes it’s a bit different. Since we already eat tomato salad, we will not eat so much sauce in the summer months, though we do eat some. However, when the tomato season is over we do like to cook with tomato sauce a lot.

The Roma tomato carries about 1 kg per week for about 5 weeks in a row. This will give us about 2 small (250 g) jars per plant per week for 5 weeks.

So 1 plant will give us about 10 jars. We’ll use the jars from November until June and use 6–7 jars a month, let’s say 45 jars in total.

From this calculation we will need 4–5 plants, but because I always go for safe I’ll plant 6–7.

Onions

For onions there are actually two systems.

In a mild climate you can plant some every month except in December and January. You’ll need about 1 reasonable-sized onion per day. So that makes 35 a month.

The other option is to plant all your onions just once a year. The amount is the same. About 1 onion a day. That is about 400 for the year.

The Rest of the July Harvest

I think you get the picture here: for the carrots, aubergines and leek, the same type of calculation as in January applies.

I made a calculation of how much each plant delivers. I use this calculation in my vegetable gardening courses, but please remember these are estimates. You can download it here.

How many vegetables do you need for 4 persons

So Far About Method 1

Well, I think you get the picture of how to figure out how many vegetables you need to plant.

By making the calendar we took into account that some plants produce in one go and others continue to produce over time. So that is important knowledge when you are making your calendar.

As you can see in the calendar, the lettuce is planted multiple times. The tomatoes and aubergines are just planted once and the carrots are sown once and then harvested bit by bit for two months.

Method 2: The Monthly Planting Rhythm

The second method is not very different from the first, but it does need a bit more experience because you are going to improvise a lot more on the spot. For this you need to be familiar with your seeding calendar, not only on paper but also in real life.

In Method 1 you decide at the start of the year how much you are going to plant from which vegetable. You write that down in your garden book and you proceed through the year.

In Method 2 you do not fix it all. It gives you more flexibility to adjust things as the year goes on. Although crops like tomatoes, aubergines and other long-season harvestable crops, as well as fixed companion-planted crops (like the corn, beans and squash), will still be sown or planted through Method 1.

How the Monthly Planting Rhythm Works

1. Check What You Still Have in the Garden

Before we go to the market to buy seedlings, or before we sow a new vegetable, we first check what we still have in our vegetable garden. We need to take into account that the seedling will only become a plant to harvest in about 4–6 weeks (in winter it might take longer), so we have to picture what will still be in the garden by that time.

2. Choose What You Want to Be Eating in the Coming Months

We go to a big market in a nearby town at the beginning of every month. There we buy seedlings at a big stall with a lot of different vegetables. Depending on what they have for sale, we choose what we would like to eat and decide on the numbers on the spot.

Example: What to Buy at the August Market?

So from what I wrote above we can conclude that what we plant and sow in August will feed you from the end of September into October or November.

Say you find the following interesting vegetables at the market:

Chinese cabbage seedlings:

- It will be ready in about 6 weeks.

- It’s harvested in one go.

- So one plant, if it reaches a good size, will give two meals for two people.

Rapini seedlings: ready for the first pick in about 6 weeks. You can keep on picking leaves from mid-September into December. Half a plant is good for a meal for two.

- Broccoli (harvested in one go)

- Red cabbage (harvested in one go)

- Lettuce

We want to buy some of these because we like to eat these vegetables.

What Grows When?

We also have to take into account that all of these mature at slightly different speeds:

- Chinese cabbage + rapini + broccoli → ready early October

- Red cabbage → slower, ready early November

- Rapini leaves → can be harvested for weeks (Oct → Dec)

Before we left, we checked what will still be growing in October:

- Aubergines (eggplants)

- Swiss chard

- Leeks

These are your October harvest partners.

Now you estimate your household’s needs.

Meal Planning Example (for Two People)

You cook about 20 meals per month from the garden.

You know roughly how much each vegetable provides:

- 1 Chinese cabbage = 2 meals

- 2 broccoli heads = 1 meal

- Rapini = 1 meal (and it regrows)

Already in the Garden:

- Aubergines = +4 meals per month

- Swiss chard = abundant backup

- We have 8 leeks = about 4 meals (or one or two big soups)

So What Do You Plant in August?

For October harvests:

- 6 Chinese cabbages → 12 meals

- 6 broccolis → 3 meals

- 6 rapini → 6 meals (plus extended picking)

- Aubergine and leek already growing

- Add 12 lettuces for salads throughout the month

This gives you roughly 20 flexible meals from the garden.

This is the whole logic:

👉 Instead of calculating backwards from yearly consumption…

👉 You plant each month the amount you want to be able to eat in the coming months.

This creates a steady, manageable rhythm—and avoids both gluts and gaps.

Now: this kind of calculation is something that you might use in the first years. For this it is important to make notes per month in your gardening book. You can then look it up the next year and adjust it if it didn’t cover your needs.

To be honest, I do not calculate the amounts anymore. I now work with estimates because I know more or less where I end up. I tend to stay a bit on the generous side since I prefer to give a few vegetables away rather than run short.

Conclusion — Two Paths, One Goal: A Garden That Feeds You Year-Round

Whether you choose the Planner for the Whole Year or the Monthly Planting Rhythm, both approaches help you create a vegetable garden that matches your climate, your lifestyle, and the way you like to eat at your table.

Both systems work, and many gardeners eventually use a mix of both.

With a bit of tuning, your garden can support you through every season—letting you enjoy fresh, homegrown food without guesswork.

If you like what you have read, consider taking one of our Vegetable Gardening courses or subscribe for our blog down here on this page.