Crop rotation is one of those gardening ideas that sounds simple, yet makes a huge difference once you truly understand it. Many problems in vegetable gardens — recurring pests, declining harvests, tired soil — can often be traced back to planting the same types of vegetables in the same place year after year.

At its core, crop rotation means not growing vegetables from the same plant family in the same bed repeatedly. When done well, it supports soil health, reduces disease pressure, and helps plants grow stronger with fewer interventions.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy Crop Rotation Matters

Every vegetable interacts with the soil in a slightly different way. Some crops take a lot of nutrients, others very little. Some attract specific pests or diseases that can survive in the soil long after the plants are gone.

When the same type of crop is grown in the same place too often, these problems slowly build up. Soil-borne diseases establish themselves, pests return more quickly each season, and plants become more vulnerable even when they look healthy at first.

Crop rotation interrupts these cycles. By changing what grows in each bed, we make life harder for pests and diseases and give the soil time to recover. Over the years, this leads to more stable harvests and a garden that largely takes care of itself.

Why Plant Families Are the Key to Rotation

One of the most common misunderstandings about crop rotation is thinking that swapping one vegetable for another is enough. In reality, crop rotation only works properly when we rotate plant families, not just individual crops.

Plants are grouped into families based on their botanical characteristics, which we see reflected in their Latin names. These families matter because pests and diseases usually target an entire family, not just one plant.

For example, cabbage, broccoli, kale, cauliflower, and radish may look very different above ground, but they all belong to the Brassica family. If a disease or pest appears in a bed, all of them are at risk.

The same applies to potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, and aubergines, which all belong to the nightshade family (Solanaceae), and to onions, garlic, and leeks, which are part of the onion family (Amaryllidaceae).

Once you start seeing vegetables as members of families rather than isolated crops, crop rotation becomes much clearer and much more effective.

When Plant Families Repeat: What Goes Wrong

Many of the most persistent garden problems are directly linked to repeating plant families too often.

Cabbage root fly, for example, affects all Brassicas. Once it establishes itself in a bed, planting any type of cabbage family crop there again simply invites the problem back. Clubroot, another Brassica disease, can survive in the soil for years and may leave a bed unsuitable for cabbages long-term.

Nightshades have their own issues. Potato blight becomes more likely when potatoes return too quickly, and the Colorado beetle attacks both potatoes and aubergines because they belong to the same family.

For this reason, most plant families benefit from returning to the same bed only once every four to six years. This sounds like a long time, but even a simple rotation across a few beds already creates meaningful distance between crops.

A Real-Life Example: Reading a Garden Rotation Plan

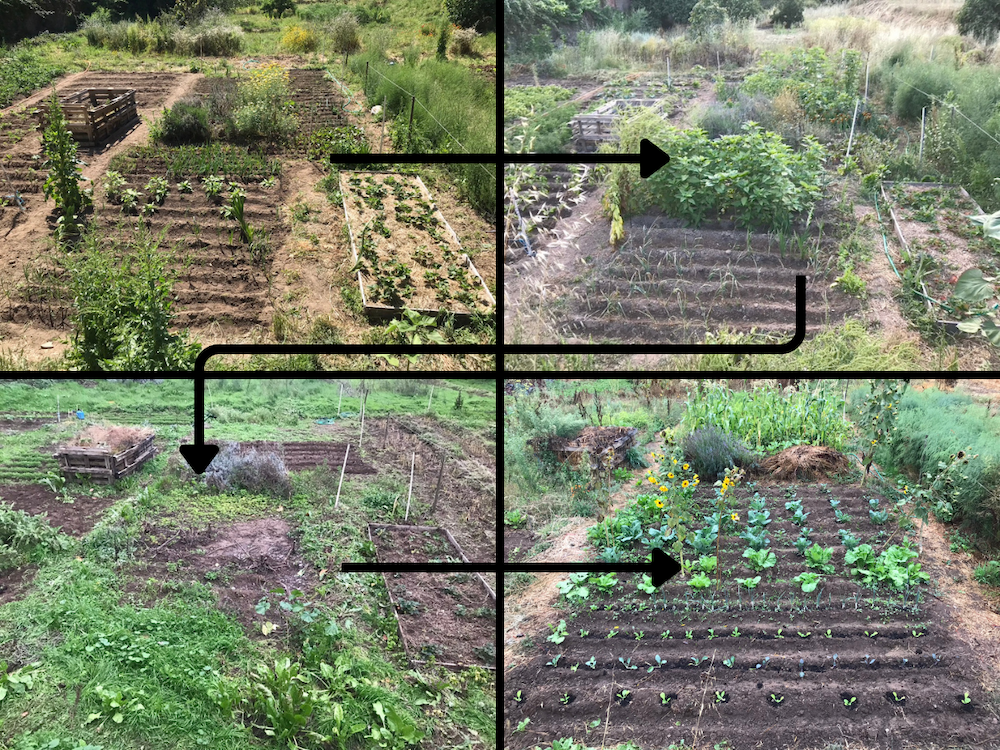

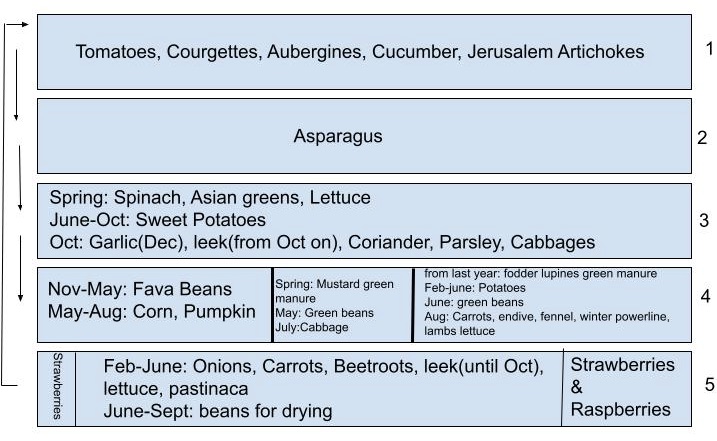

The garden rotation plan shown in the image is an example of how these ideas come together in a real, working garden.

Each long bed represents one growing area. The crops listed inside each bed show what grows there throughout the year, often in succession rather than all at once. The arrows show how the beds rotate from one year to the next, so plant families move through the garden instead of staying in the same place.

Some beds are clearly marked as permanent or semi-permanent, such as asparagus, strawberries, and raspberries. These crops stay in one place for many years and are therefore excluded from the annual rotation. This is an important distinction: crop rotation applies to annual vegetables, not perennials.

Other beds show how multiple crops can follow one another within a single year. A bed might start with quick spring greens, continue with a summer crop like sweet potatoes, and finish the year with garlic or winter vegetables. Even though many crops grow in one season, careful planning avoids repeating the same plant family unnecessarily.

This kind of plan shows that crop rotation is not rigid. It is a guiding structure that helps you make good decisions while still allowing flexibility.

Crop Rotation and Soil Fertility

Crop rotation is closely linked to how we manage soil fertility. Different plant families have different nutrient needs, and a good rotation uses this to the soil’s advantage.

Heavy-feeding crops such as cabbages, tomatoes, and pumpkins thrive in beds that receive generous compost. Crops that follow them can often grow well using the nutrients that remain. Legumes, such as beans and peas, play a special role by fixing nitrogen and improving soil structure rather than depleting it.

By rotating crops in this way, compost is used more efficiently, and the soil remains fertile without constant external inputs. Over time, this creates a natural rhythm that supports both plants and soil life.

Why Potatoes Are a Useful Starting Crop

Potatoes are often an excellent first crop when opening new ground or establishing a new rotation. They are robust plants that suppress weeds, tolerate fresh manure, and help loosen the soil.

Starting with a small potato bed allows you to prepare the ground while setting up your future rotation. The following year, potatoes move on to a new bed and a different plant family takes their place. This simple step already introduces rotation into the garden.

Crop Rotation as a Living System

Crop rotation is not a fixed formula. It is a long-term strategy that evolves as your garden grows and as you learn more about your soil, climate, and plants.

By focusing on plant families, allowing time between repeats, and combining rotation with thoughtful compost use, you build a garden that becomes healthier and more resilient every year.

A good rotation plan is not about perfection — it is about working with nature, season by season, and letting the garden improve over time.

Frequently Asked Questions About Crop Rotation

Crop rotation means changing the location of plant families in your garden each year instead of growing the same types of vegetables in the same bed repeatedly. The aim is to keep the soil healthy, reduce pests and diseases, and balance nutrient use over time.

Crop rotation helps prevent soil-borne diseases, reduces pest pressure, and improves soil fertility. Gardens that rotate crops regularly usually produce stronger plants and more reliable harvests with fewer problems.

A common guideline is to wait four to six years before returning the same plant family to the same bed. If you grow multiple crops in one bed each year, think in terms of four to six different crops before repeating the same family.

Yes. Even in a small garden, crop rotation makes a noticeable difference. You may not achieve a perfect long cycle, but simply avoiding planting the same family in the same place every year already reduces many common pests and diseases.

Plant families are botanical groupings of related vegetables, such as the cabbage family, nightshade family, or onion family. They matter because pests and diseases usually affect an entire family rather than a single crop, which is why rotation works best at family level.